A Mother's Seed: A Reflection on 'Kura Uone' in Conversation with Wallen Mapondera

- Misha Krynauw

- Mar 24

- 7 min read

by Misha Krynauw

Molly Kativhu, Wallen Mapondera’s mother, is not only at the heart of his latest solo presentation with SMAC Gallery in Cape Town, but the artist’s practice, too. “My mother is the source, the inspiration and the support to my practice,” Mapondera insists. Through a thematic score of faith, grief, love and regeneration, the artist primarily uses found materials that have been reduced to waste. Whether organic or man and machine-made, once discarded, they fall into the scope of the artist’s consideration for the composition of his vision. Ranging from egg cartons to palm tree seeds, baize, tent tarp, cardboard and more, Mapondera takes a technical and methodical approach along with his studio assistants to assemble the terms of his reflections on our zeitgeist.

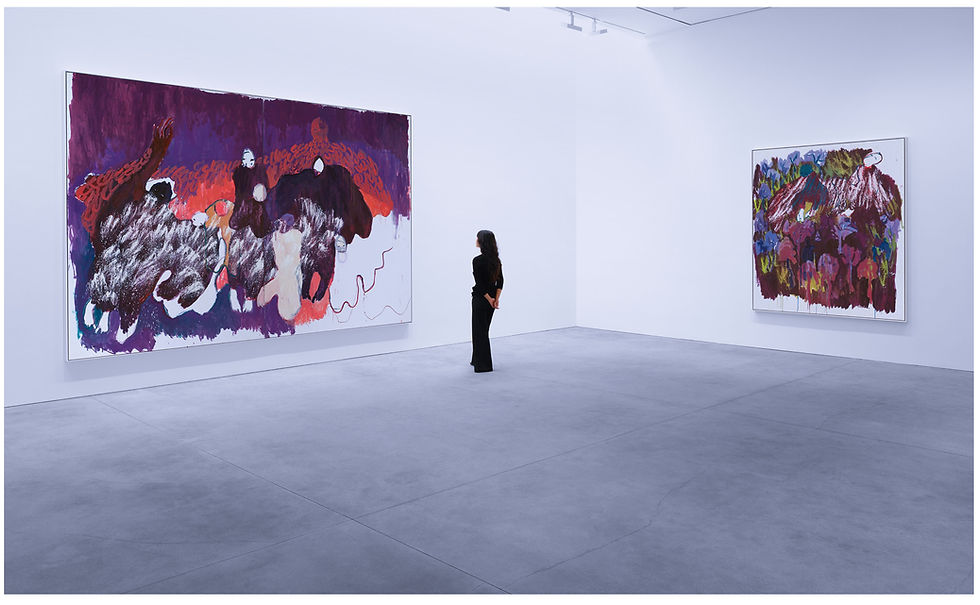

Invested in the matter of now, Mapondera not only uses what he finds, but also what he feels, receives and discovers. Choosing a series of symbols from the vast variety of our failures against our environment, capitalism and consumerism are the ink and paper of Mapondera’s records. An avenue of inquiry into ancestral knowledge occurs somewhere in-between, while the artist remains steadfast in keeping his emphasis on “today”. Kuvavarira Hutsvene, 2024, a series of five conjoined panels of collated egg carton cut-outs, creates a rhythmic frequency through folding and gluing reminiscent of rippling currents. The show title, Kura Uone, translates to mature, or grow up, and then see. Opened during the annual Investec Cape Town Art Fair 2025 at SMAC Gallery, the solo exhibition departed from the expanse of the first floor of the storied building, across its levels and the artist’s work’s dimensions and colours.

Hurongwa (Plan), 2024, is a sculpture of cardboard assembled with waxed threads from Cape Town’s own Woodheads. Hanging from two metal rods, the piece emulates visually —at least to me— two hands crocheting, as his mother would when creating her doilies, a cornerstone of Mapondera’s creative memory. Immediately, I became interested in the colour palette on display, one that relies so heavily on what has already been decided, or provided rather. With Mapondera’s painting, I was curious how those specific incorporations were made.

“I put a few colours on a painting, or subjects that I’m thinking of painting, then there comes a moment where you have to wait, and get into a dialogue with the painting. Now it has to direct you to what it wants. Most of the time the image that you have in your head won’t come out as what you’ll have on the painting, because you might want to use blue, but blue won’t work [for example]. The painting becomes the director, it shows you what it wants to become,” Wallen explains.

Misha Krynauw: How would you describe the symbolic nature of your visual language, and your approach to it, in relation to materiality?

Wallen Mapondera: Repetition is an essential part of my working process. The repetitive act of cutting and stitching multiple pieces of cardboard together, as well as the repetition that the viewer sees in the finished object, symbolizes repeated daily acts such as eating, cooking and washing dishes. It also alludes to the frequency of a persistent salesperson who shouts out when calling customers in spaces like Mupedzanhamo, a marketplace in Mbare where bales of second-hand clothes are sold. The owners of the bales hire untrained people with natural selling expertise. Some of these vendors even compose songs.

The level of detail encoded into the meaning of these materials are a kind of storytelling that some are more fluent in than others.

MK: With this latest solo presentation at SMAC gallery which overlapped the city’s annual Investec Cape Town Art Fair, Kura Uone, welcomed audiences to consider faith as its ritual of spiritual rite beyond surviving capitalism. How would you describe your sense

of faith, and how would you describe that of your mother?

WM: My mother is a devoted and unshaken Christian. She nurtured us (her children) that way in our upbringing and we have been in that faith ever since. Colonization had a major influence in disrupting our culture by reducing and minimizing our ways of praying through introducing Christianity to us. I think I missed a lot from our culture and our ways of doing things, hence I am interested in knowing what our forefathers believed in before colonization that made a whole meal pop out from a tree when begged for.

MK: “Mature and then see”, what is your first memory of this phrase?

WM: My first memory of this phrase is a collective of events from a specific period and time in 2005. I had to walk a distance of about 16 kilometers to and from Art College. This was the period when a lot of basic commodities such as sugar, cooking oil, corn and fuel were scarce in the country. Transport fares became insanely expensive as a reflex to the fuel shortage. It became a norm to join any queue we find on shop entrances with the hope of finding any of these basic commodities. The sale of sugar or cooking oil was

limited per person so that a lot of people will be served. Sometimes we could join the queues based on an announcement that the shop owners would have made with regards to delivery time of the items. Being in a queue all day and returning home hungry and empty handed was the most painful part.

MK: Using found materials and engaging with some version of recycling and regeneration, what has the labour of your practice taught you about human consumption?

WM: I can study a lifestyle by just going through someone’s trash. You can tell what they eat, what they like, what they use, that kind of thing. Most of it is unhealthy, because that’s affordable.

In this sense, Mapondera’s work becomes an interpretation of labour as much as human behaviour, illuminating the reality of capitalism and consumerism in a tangible manner. Closing the distance many enjoy in separation from the consequences of their actions from the virtue-signalling pollution and socio-economic politics has been reduced to online.

MK: Please describe your relationship to the objects and patterns (if any) that you return to in your works.

WM: Memories are awakened by objects, which make people relate to them more and in turn give the objects meaning. To me, it could be the object’s shape, scent, reference or purpose that triggers memories of how I may have engaged with the objects physically, psychologically or spiritually in the past. I work intuitively with the material so that it leads me into the best possible effective outcome as I connect and engage in a conversation with the material through researching its past and present purpose. The process

may take hours or days, and sometimes it can take months to years depending on how rapidly the material and I link. In the exhibition Kura Uone, I borrowed the patterns from doilies that my mother used to make. I redefined them and came up with patterns that lay between craft and contemporary.

MK: Kura Uone is described by Azu Nwagbogu as a, “profound collaboration between [you] and [your] mother.” Your intention to honour your lineage and community permeate your work, but this particular effort to honour your mother with this presentation is very moving. How did this particular intention and presentation materialise for you?

WM: When I was working on this body of work, I had initially planned for a solo exhibition where I was focusing on the role that my mom played to help the family survive. My dad was employed and my mom was not. She always addressed herself as a housewife. I am the 5th and the last born in our family, I cannot [say] that my mom was only a housewife, she was that and more. I grew up knowing that my mom is a cross-border trader. Her craft was to make doilies and clay pots, [and she] took them to South Africa, Zambia and Mozambique to sell them on that side and came [back] with clothes, food and money.

The journey to these countries was not as smooth as it sounds. They were packed with struggle, starvation, prayers, and sometimes joy. I have done some doilies inspired artworks before, but I felt I have not exhausted them enough when I bumped into one of the doilies that my mom made. The questions I was asking her about her trips to the neighboring countries sparked her curiosity and she wanted to know more. I explained my upcoming solo exhibition to her and she got even more fascinated, to the extent of wanting to become a part of it. Fun fact is [that] she says I inspire her to make art, yet I think I inherited her craftsmanship. There is an element of exchanging roles: she was there always to nurture us when we were growing up and now she comes to me for critique when she has made some artworks and for advice.

On the heels of the Investec Art Fair, the brainchild of Mapondera, Admire Kamudzengerere, and curator Merilyn Mushakwe, with Laura Ganda serving as the curator, took the form of the inaugural Cheuka Harare Art Fair (CHAF). The auspicious occasion took place from February 27 to March 1, 2025, at the Andy Miller Hall in Harare Showgrounds. “I am more interested in helping other artists, that’s where my passion is,” Mapondera explains of the next channel for his creative expression.

MK: How would you describe Zimbabwean art’s audienceship as a culture?

WM: It is a bit closed and not accessible for everyone, and there is a stereotype of it being for the elite. There are not that many people, but the audience is there. My main fight is for wealthier Zimbabweans to understand [our] art so that they can invest in it, and not wait [only] for the CPT art fair. There hasn’t been an art fair in Zimbabwe [before, so], there was nothing to come for. This is where we can grow from.

MMK: Your first presentation was 27 years ago now, how has time added depth —beyond technique— to your practice?

WM: Time gave me understanding, connections, patience, innovation and curiosity through different lived experiences, which I vent through my work.

MMK: Egg crates are a prominent material in this presentation. May I invite you to reflect on the symbolism of the egg in its absence; what does the egg represent to you and what is the significance of it that you’re seeking to impress on us?

WM: To me, the egg is a seed: it represents life and death.

The artist presents his audience with a moment at a length of their own choosing to consider the dimensions of human expression, even in these subconscious, coerced, consumer-driven channels of our expression. We define ourselves in our determination to have the world around us defined by its use to us.

What we discard speaks of us, as well.

Kura Uone.

Misha Krynauw is a South African poet, essayist and art writer.

Comments